|

| In the Dead of Night, The Reeds Speak of Separation, Bradley, 2017. Digital print on silk coated digital paper. 100x300cm |

“Further away from the wolf pen, we made a more balanced recording of all the morning’s singers with whom the wolves had been calling. By making the same recording overnight from the leopard enclosure, we were able to hear more of the finer animal calls in the mix. Expanding the sound, I discovered a blip in the timeline, a rising and falling, a cacophony of creatures, calling up to the sky. I then had to work out whether whether it was the airplanes that had set off this morning cacophony or something else. It was in fact, the first azaan, before the call to prayer, in the distance which can be heard faintly at the start and end of the collective racket made by the animals.

One can see the shape of the sound, rising up out of the darkness, is much fuller for the chorus and resembles to my mind the very mosque it is singing along with, or perhaps masking. Have the animals become the sketchers of the acoustic footprint of the mosque itself, creating their own architecture in space but with sound?

|

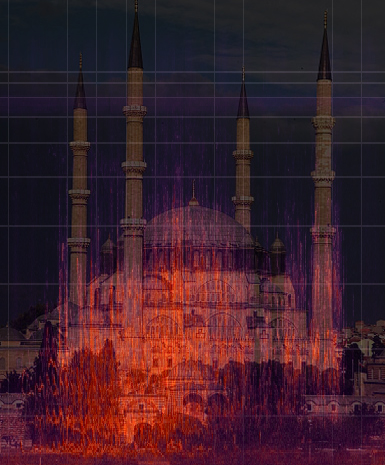

| In the Dead of Night, The Reeds Speak of Separation 2, Bradley, 2017. Digital print on silk coated digital paper. 100x100cm |

The azaan is a sound one hears everywhere, even in desert outposts

makeshift and resplendent mosques alike pepper the landscape. I was born

in Iran and for me the azaan played out 5 times a day for the first

formative years of my life, it somehow gets under the skin. The praying

face East from wherever they are, like migratory birds who know the

direction of north, south, east, west, wherever you place them, the one who

prays must orientate themselves. The prayer, conducted at the same time each day

brings people together, it is said ‘to remember their purpose in life’, a

reminder of their collective humanity, of their oneness. So how do the

animals react to this circadian ritual of acousmatic sound? In a situation in which they cannot walk away, the azaan becomes part of their own daily ritual. Here is

evidence that the animals join in, and enunciate in unaccompanied

crescendo. Needing no amplification, they do not sing, but rather call out in complete darkness, a time when sound carries further than any other during the day and has

more agency. The different species call as one, to whom we do not know, call to all free animals, who too join in. We often discuss

the voices of animals but less what they hear, yet certainly they are

hearing, first the azaan, then themselves, then their cacophonous unity,

and with that collective sound they supersede the boundaries of their

cages. The inhabitants of the wildlife centre making their acoustic

footprint larger than the limits of the ones they are able to make in

the desert sand, sending their

sound up like a free bird, or the souls that Persian Sufi poet Jalal aldin Rumi compares

often to a bird.

“The soul is like a falcon and the body chains,

a slave that’s bound of foot and broken winged.”

Mathnawee

Rumi’s

spiritual ornithology compares mankind unfavourably to the spirit, which

is a falcon, who would return to the arm of the king, i.e. the divine. Yet to Rumi

humans are only owls (fowls), they are not falcons. Here in The Capturing of the Falcon Among the Owls

in the Wilderness

(Mathnawi, book II):

O all you disputatious fowls, be falcons

and listen to your royal falcon-drum

From your diversity to unity

set out from all directions joyfully!

|

| In the Dead of Night, The Reeds Speak of Separation 3, Bradley, 2017. Digital print on silk coated digital paper. 100x100cm |

But most of all it is Rumi’s flute, which resembles the expression

of the soul yearning to return to its state of oneness, which I hear

amongst the animals before dawn. I returned to this poem as I know it

very well, having performed it several times including at Cafe Oto and the

Delfina Foundation London. Here in his poem, Rumi describes the throat as the flute, the utterance that links us, that calls to return to the

divine, while the voiceless fish (the spiritually dead mystics – religious authorities -, who cannot fly, nor use the air to carry up their call) being blind to what is all around them, are unable to satisfy this longing:

Listen to the story told by the reed,

of being separated:

“Since I was cut from the reedbed,

I have made this crying sound.

Anyone apart from someone he loves

understands what I say.

Anyone pulled from a source

longs to go back.

At any gathering I am there,

mingling in the laughing and grieving,

a friend to each, but few

will hear the secrets hidden /

within the notes.

No ears for that.

Body flowing out of spirit,

spirit up from body: no concealing /

that mixing.

But it’s not given us

to see the soul.

The reed flute

is fire, not wind. Be that empty.”

Hear the love-fire tangled

in the reed notes, as bewilderment

melts into wine.

The reed is a friend

to all who want the fabric torn

and drawn away.

The reed is hurt and salve combining.

Intimacy and longing for

intimacy, one song

A disastrous surrender,

and a fine love, together.

The one who secretly hears this

is senseless. A tongue has

one customer, the ear.

If

a sugarcane flute had no effect,

it would not have been able to make

sugar

in the reedbed. Whatever sound

it makes is for everyone.

Days full of wanting, let them go by

without worrying that they do.

Stay where you are, inside

such a pure, hollow note.

Every thirst gets satisfied except

that of these fish, the mystics,

who swim an ocean of grace

still somehow longing for it!

No one lives in that without

being nourished every day.

But if someone doesn’t want

to hear the song of the reed flute,

it’s best to cut conversation

short, say goodbye, and leave.